In 1863 a human heart was found enclosed in a lead cyst within the crypt. It was uncovered when a workman was lowering a portion of the foundation of a pillar from the old church. In a recess he found the heart resting on a coffin lid, which had a metal plate with ‘1549’ inscribed up on it.

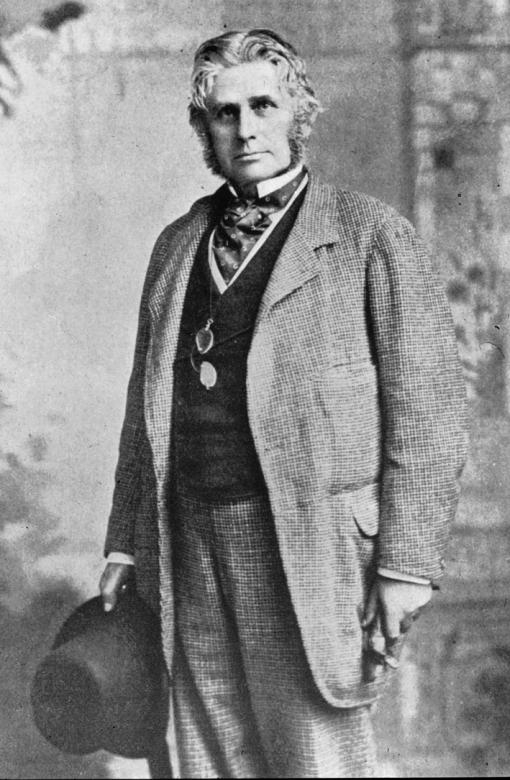

The heart was later obtained by General Pitt Rivers when he was stationed in Ireland between 1862 and 1866. General Pitt Rivers (1827 –1900) was an English army officer, ethnologist, and archaeologist who donated his entire collection of artefacts to the University of Oxford. The heart which formed part of this donation is now exhibited in the Pitt Rivers Museum, one of the world’s greatest collections of artefacts.

The lead cyst has no information as to whose heart resides within. It is not known how long the heart remained entombed in the crypt. Neither is it known what station in life the owner of the heart occupied in life, nor if it was a religious rite or sentimental gesture.

What we do know is that for the medieval mind-set the heart represented the entire body and functioned as the receptacle for the record of a man’s life. Separate burial of the heart is a funerary practice based on mystical belief in the power of the heart. The practice of heart burial derives thus from the soul and human consciousness being associated with the heart. The part most sought after, the noblest part, was the heart, the secret of life and emotion.

The funerary practice of heart removal and separate burial was a widespread custom among the elite classes of northern medieval Europe, amongst royalty, nobility, warriors and ecclesiastics and nobles who died away from home. In this context we can imagine that the owner of the heart may have died far from the parish of Christchurch, the body was buried abroad and the heart was brought back for burial in Cork.